On a sunny weekday in May, my mom and I are driving down Old Sudbury Road in Lincoln, Massachusetts. It’s the first day of our four-day road trip through New England, and she’s opted to be surprised by the stops I’ve added to our itinerary. We’re 35 minutes and a world away from the historic homes and notorious traffic of Boston. The road is mostly bordered by farmland; fences of various heights keep cows and sheep from straying too far from home and their grazing pastures.

Key Takeaways

- Ponyhenge in Lincoln, Massachusetts features more than 30 toy rocking horses that have intrigued visitors since 2010.

- The display began when landowners left a Headless Horseman prop in their field after a Halloween celebration.

- New horses mysteriously appear and are rearranged into creative formations for holidays, races, and other playful themes.

When I pull off into a dirt patch on the side of the road and declare that we’ve reached our destination, my mom is indeed surprised. She surveys the empty expanse for signs of life—or the types of roadside attractions with which I usually pack our trips—and finally she spots it: a neatly arranged ring of tiny horses.

What is Ponyhenge? Location and Quick Facts

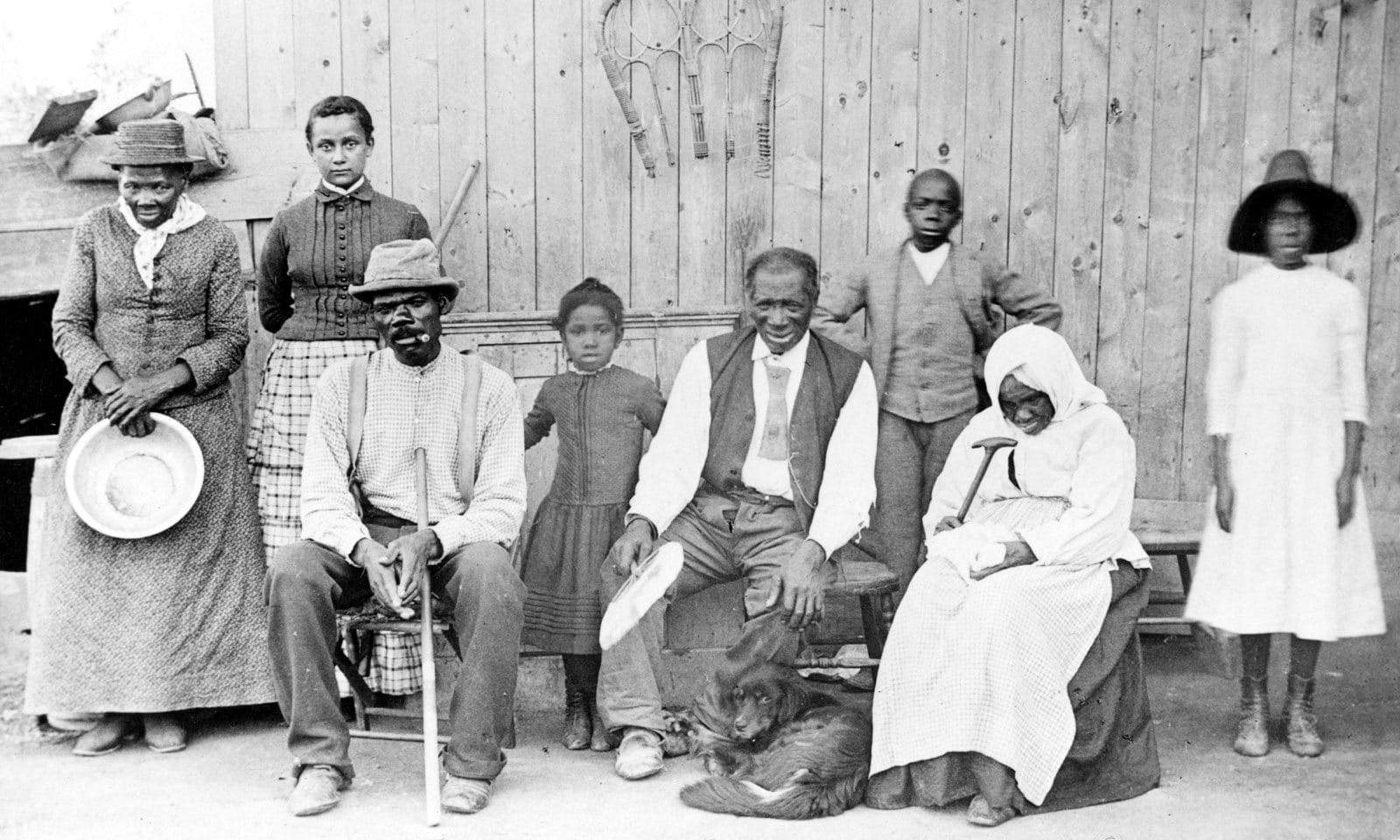

Live horses would not be an unexpected sight on this rural road, but the horses in this particular field were never alive. We have arrived at Ponyhenge, a collection of more than 30 toy rocking horses that has been puzzling and delighting locals and tourists since 2010.

Ponyhenge History and Mystery

Almost everyone has heard of Stonehenge, the prehistoric monument and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Wiltshire, England. But unless you’re a resident of Northeastern Massachusetts, you may not be familiar with the area’s less-ancient, but more playful version of objects arranged mysteriously in a field.

The word “henge” first appeared in the mid-18th century as a back-formation from the word Stonehenge, which itself is derived from the Middle English words for “stone” and a version of the word “hinge.” “Henge” is now defined by the dictionary more loosely as “a prehistoric monument consisting of a circle of stone or wooden uprights.”

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

New England’s version of the old England attraction—also known as the Rocking Horse Graveyard—is constantly in flux but one thing is certain: Like its counterpart across the pond, no one quite knows how or why so many toy rocking horses ended up in a field in Lincoln. Many locals, however, seem content to have its exact origins remain a mystery.

Origin Story: From a Headless Horseman Prop to a Local Landmark

Megan Kate Nelson is a writer and historian who lives in Lincoln and regularly runs and cycles by Ponyhenge. “At first, there was just one rocking horse in the middle of the field, which had its own kind of romantic aesthetic,” she says.

Who Owns the Ponyhenge Field?

James Pingeon and his wife Elizabeth Graver own the land on which the ponies sit, and live next door. Pingeon told the Boston Globe that the installation grew from a Headless Horseman prop discarded after a Halloween celebration.

“It started out where we had a little Halloween show, and they had a Headless Horseman in the field, and we didn’t know what to do with the horse afterward,” he told the Globe. “So we thought, ‘Oh, let’s just leave it in the field.’”

Community Art That Keeps Growing

Ponyhenge may have been started by just one or two people, but today it exists as a collaboration between many. Over the years, more and more horses of inexplicable origins have appeared. Nelson says at one time there were nearly 50 horses, but today the number is closer to 30. Some of the horses are plastic, some are wooden; most have saddles and string reins; some look modern and others might qualify as antiques.

New Rocking Horses Appear Anonymously

“Other people started leaving them, and we just didn’t want to know,” Graver told the Globe. “There was something lovely about it being anonymous, and now every time we go away, another one appears.”

Seasonal Ponyhenge Arrangements and Playful Themes

Taken individually, the horses—with their rusty springs, shredded manes, and peeling paint—could be mistaken for trash. But put dozens of similar items together and the result becomes a collection. A group is usually much more than just the sum of its parts, and the same can be said for Ponyhenge. Before my visit, I had no idea there were so many different styles of toy rocking horses in the world, let alone in a small town like Lincoln (the human population hovers around 6,000).

“I think most people living in Lincoln think of Ponyhenge as another quirky element of the town,” says Nelson. “We regularly elect a town Measurer of Wood and Bark and a Fence Viewer.”

The herd has not only grown in the last nine years, but the horses have been known to change positions unexpectedly. Like a less-labor-intensive crop circle, no one is quite sure who moves the residents of Ponyhenge, but every so often they are rearranged into a new formation.

“Once there was a critical mass of around ten horses, people would start arranging them into groups,” says Nelson. “After the 2016 presidential election, a few of the horses began to sport ‘pussy hats.’ Clearly, people are bringing their own interests to Ponyhenge.”

Nelson has documented the ever-changing installation throughout the years. For the Kentucky Derby, she says that the horses were moved into lines, waiting for a starting gunshot that presumably never came. After Labor Day (when school starts in Massachusetts), the horses were arranged in rows as if they were in school. They’re draped in lights at Christmas, and sometimes they’re buried completely by snow during the harsh New England winters.

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

When we visit, the horses are arranged like their ancient namesake, more or less in a circle. I’m surprised at how close the horses are to the road and neighboring houses—I had expected to trek through an inhospitable field, but I feel as if I’m in someone’s backyard (the land is privately owned, but respectful visitors are allowed). The grass surrounding each horse is overgrown, but the rest of the field is well-maintained.

How Ponyhenge is Cared For

According to Nelson, Pingeon and Graver do assert some control over Ponyhenge. They mow the grass and have placed rocks near the road to keep cars from disturbing the horses. They also “cull the herd every few years, getting rid of really derelict horses,” says Nelson.

Why Ponyhenge Delights New England Roadtrippers

Discarded childhood toys are uniquely powerful reminders of our own mortality and the unrelenting march of time. I’m not at Ponyhenge long before its weathered painted ponies remind me of this verse in the Joni Mitchell song “The Circle Game”: “And the seasons they go round and round / And the painted ponies go up and down / We’re captive on the carousel of time / We can’t return we can only look behind / From where we came.”

A few cars drive by and a man slowly passes on a tractor, but otherwise we have this small plot of land to ourselves. You could pass by Ponyhenge and never see it, disregard it as a dumping ground, or mistake it for a pop-up playground. There’s nothing to do at Ponyhenge except to look and wonder—but the point of many roadside attractions is that there is no point.

“It is a place that exists only to bring joy—and we have too few of these places in American culture.”

“To me, Ponyhenge is a really charming, spontaneous art installation,” says Nelson. “Regular people feel moved to contribute to the site of their own volition. I often ride by to find parents taking pictures of their children romping among the horses. It is a place that exists only to bring joy—and we have too few of these places in American culture.”

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Ponyhenge may not be as popular or as historically significant as Stonehenge, but it’s certainly more whimsical. Those who do take the time to stop are rewarded with a colorful photo-op, a beautiful landscape over which to stretch your legs, and a brief moment of solitude to ponder a local mystery.

You may not be able to slow down the carousel of time, but should you ever find yourself in Lincoln, Massachusetts, pull over, stop the car, and take a moment to appreciate an art installation born of the ingenuity and camaraderie of complete strangers.

Plan Your Visit to Ponyhenge, Lincoln MA

Ponyhenge is located on private property so be respectful of the neighbors and surrounding land.